By Nick Routley / Carmen Ang

One of the hallmarks of democratic society is a healthy, free-flowing media ecosystem.

In times past, that media ecosystem would include various mass media outlets, from newspapers to cable TV networks. Today, the internet and social media platforms have greatly expanded the scope and reach of communication within society.

Of course, journalism plays a key role within that ecosystem. High quality journalism and the unprecedented transparency of social media keeps power structures in check—and sometimes, these forces can drive genuine societal change. Reporters bring us news from the front lines of conflict, and uncover hard truths through investigative journalism.

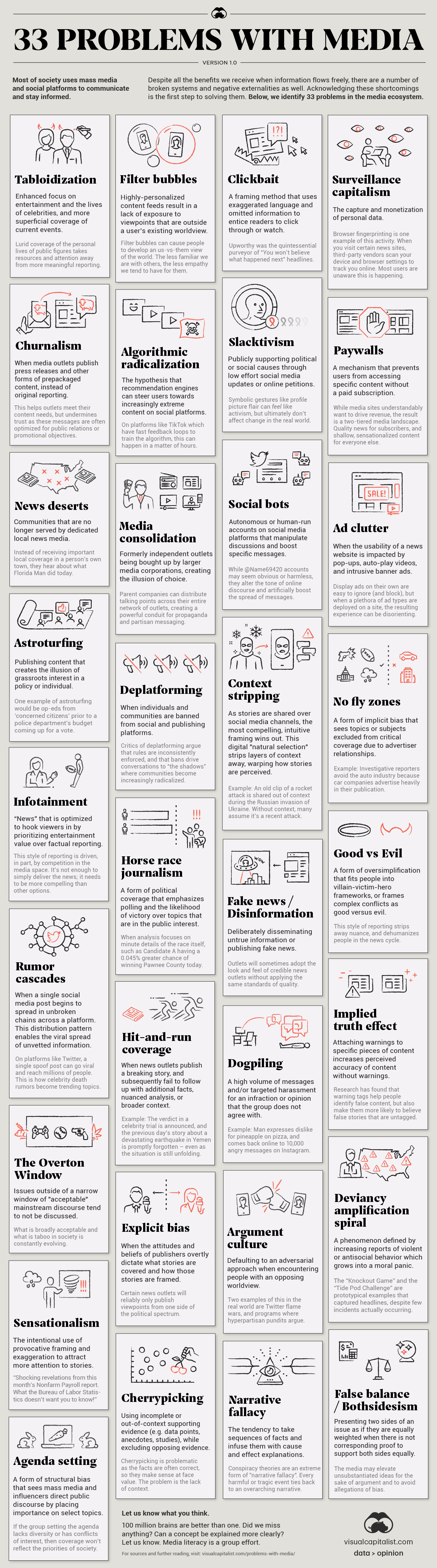

That said, these positive impacts are sometimes overshadowed by harmful practices and negative externalities occurring in the media ecosystem.

The graphic below is an attempt to catalog problems within the media ecosystem as a basis for discussion. Many of the problems are easy to understand once they’re identified. However, in some cases, there is an interplay between these issues that is worth digging into. Below are a few of those instances.

Explicit Bias vs. Implicit Bias

Broadly speaking, bias in media breaks down into two types: explicit and implicit.

Publishers with explicit biases will overtly dictate the types of stories that are covered in their publications and control the framing of those stories. They usually have a political or ideological leaning, and these outlets will use narrative fallacies or false balance in an effort to push their own agenda.

Unintentional filtering or skewing of information is referred to as implicit bias, and this can manifest in a few different ways. For example, a publication may turn a blind eye to a topic or issue because it would paint an advertiser in a bad light. These are called no fly zones, and given the financial struggles of the news industry, these no fly zones are becoming increasingly treacherous territory.

Misinformation vs. Disinformation

Both of these terms imply that information being shared is not factually sound. The key difference is that misinformation is unintentional, and disinformation is deliberately created to deceive people.

Fake news stories, and concepts like deepfakes, fall into the latter category. We broke down the entire spectrum of fake news and how to spot it, in a previous infographic.

Simplify, Simplify

Mass media and social feeds are the ultimate Darwinistic scenario for ideas.

Through social media, stories are shared widely by many participants, and the most compelling framing usually wins out. More often than not, it’s the pithy, provocative posts that spread the furthest. This process strips context away from an idea, potentially warping its meaning.

Video clips shared on social platforms are a prime example of context stripping in action. An (often shocking) event occurs, and it generates a massive amount of discussion despite the complete lack of context.

This unintentionally encourages viewers to stereotype the persons in the video and bring our own preconceived ideas to the table to help fill in the gaps.

Members of the media are also looking for punchy story angles to capture attention and prove the point they’re making in an article. This can lead to cherrypicking facts and ideas. Cherrypicking is especially problematic because the facts are often correct, so they make sense at face value, however, they lack important context.

Simplified models of the world make for compelling narratives, like good-vs-evil, but situations are often far more complex than what meets the eye.

The News Media Squeeze

It’s no secret that journalism is facing lean times. Newsrooms are operating with much smaller teams and budgets, and one result is ‘churnalism’. This term refers to the practice of publishing articles directly from wire services and public relations releases.

Churnalism not only replaces more rigorous forms of reporting—but also acts as an avenue for advertising and propaganda that is harder to distinguish from the news.

The increased sense of urgency to drive revenue is causing other problems as well. High-quality content is increasingly being hidden behind paywalls.

The end result is a two-tiered system, with subscribers receiving thoughtful, high-quality news, and everyone else accessing shallow or sensationalized content. That everyone else isn’t just people with lower incomes, it also largely includes younger people. The average age of today’s paid news subscriber is 50 years old, raising questions about the future of the subscription business model.

For outlets that rely on advertising, desperate times have called for desperate measures. User experience has taken a backseat to ad impressions, with ad clutter (e.g. auto-play videos, pop-ups, and prompts) interrupting content at every turn. Meanwhile, in the background, third-party trackers are still watching your every digital move, despite all the privacy opt-in prompts.

How Can We Fix the Problems with Media?

With great influence comes great responsibility. There is no easy fix to the issues that plague news and social media. But the first step is identifying these issues, and talking about them.

The more media literate we collectively become, the better equipped we will be to reform these broken systems, and push for accuracy and transparency in the communication channels that bind society together.

This article was first published on Visual Capital

MARKETING Magazine is not responsible for the content of external sites.